For professional reasons I belong to several boating groups on Facebook. One of them—a sailing and cruising group—has an element generally lacking in the others, a surfeit of ignoramuses and pirate wannabees. Although I’ve been submerged in the trawler world for 15 years, I’m still a sailor, too, and I own a 41-foot ketch. I always thought sailors were the competent, thoughtful ones on the water. Not so much nowadays apparently, as I recently found during an online discussion of night vision.

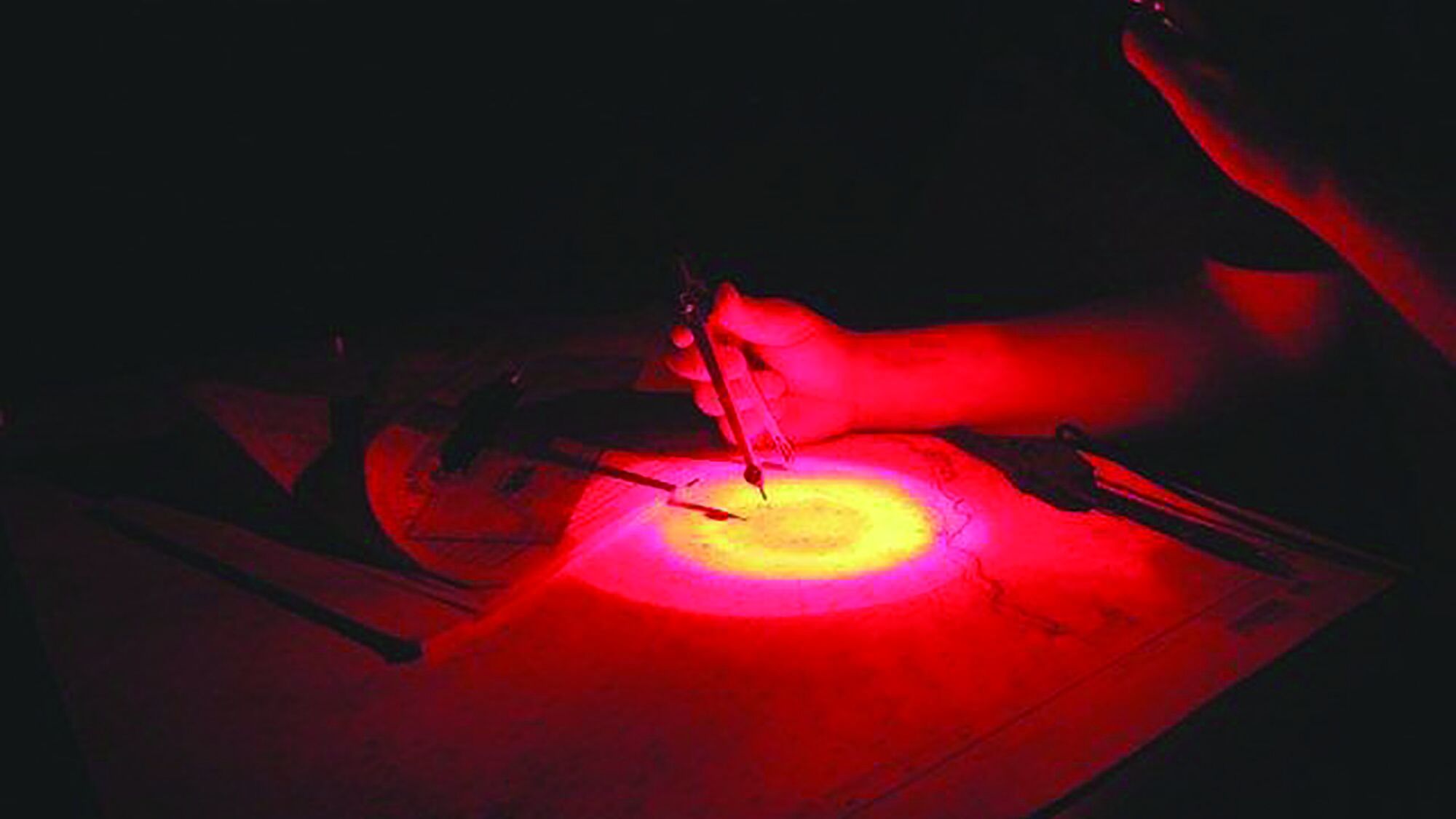

Night vision, otherwise known as “dark adaptation” has been an interest of mine ever since the Ranger sergeants staged a demonstration showing one of their colleagues smoking a cigarette on a blackened ridgeline a mile away. Night vision was of obvious importance as I began making night passages more than 40 years ago. So when someone polled the Facebook sailing group about which color lights were best for night running, I followed the comments thread with interest.

Nearly all responders endorsed red lighting, which is understandable since the marine industry has been marketing red lighting as a way to preserve night vision since World War II. The responders were unaware that “rig for red” has been demoted from best practice to “better than nothing.” Dr. Anita Rothblum, a U.S. Coast Guard expert on maritime accidents, called the red lighting initiative on warships and submarines “a scientific blunder” on the part of World War II experts.

RODS AND CONES

In “Night Vision and Nighttime Lighting for Boaters,” Rothblum writes, “In order to see a ship in the distance on a cloudy night, we need our rod vision. But in order to read charts and ARPA or (electronic charting) displays, we need our cone vision. And we can’t have both at the same time.”

She explains the origin of red lighting for night operations: “Around World War II scientists were trying to figure out how to light Navy ships and submarines so that mariners could see well at night. Someone noticed that the relative spectral sensitivity curve appeared to show that rods were almost insensitive to red/orange light…whereas cones were still fairly sensitive.….Thus was born the concept of “rig for red”: the hypothesis was that if we used red lighting at night, we would be able to read charts and still protect our sensitivity in the dark. Unfortunately, this is not the case…”

As Rothblum notes, “Red text on a white background–easily readable under white light–may appear uniformly red (and therefore unreadable) under red light, because they both reflect red light equally well. Thus, it is impossible to read color-coded charts and displays accurately under red illumination.”

In addition to causing eye fatigue, making it harder to focus, red lighting may also have a negative psychological effect, especially when a situation is stressful, according to Rothblum.

Rothblum’s paper was informed by mid-1980s research at the U.S. Naval Submarine Medical Research Laboratory, which concluded that dim white light was preferable at sea. Major navies are switching to dimmable white (and now green or blue, too) lighting for night operations, and the rest of us should consider doing the same. Rothblum concurs, noting: “Recreational and commercial mariners should consider the advantages of using low-level white light on the bridge at night…When charts and displays need to be viewed, low-level white lighting greatly surpasses red lighting in supporting good color discrimination and, therefore, accurate reading of charts and displays.”

LOW-TECH SOLUTION

Rothblum also offers a quaint suggestion for improving night vision—and it’s one that might appeal to the pirate wannabees in the Facebook sailing group. “The two eyes adapt independently of each other,” she writes. “To maintain the greatest degree of dark adaptation, one can place a black patch over one eye before turning on lights to read charts and displays.”

Rothblum explains the science behind this seemingly fanciful suggestion: “The patched eye will retain its level of dark adaptation (if little or no light leaks under the patch), while the unpatched eye can read the charts. When the lights are turned off again, take the eye patch off. The eye that was exposed to the light will need time to readjust to the dark. However, the eye that was patched will already be at or near its peak sensitivity.”

This just happens to be one of the theories behind the many portrayals of pirates wearing eye patches. Pirates may have worn eye patches just as Rothblum suggested: to preserve night vision as they moved from lighted to unlighted parts of their ships or engaged in night fighting.

Presented with the detailed evidence by some of the world’s leading experts on the topic, thoughtful sailors might be expected to react by saying, “Hey, wow! I never knew that.” But no. Several Facebookers continued to advocate for red because (I guess) their 1980 Hunter 36 came with a red bulb over the nav station and another over the compass.

Red night lighting is not going to kill you. You’ll be fine holding a course with red over your Ritchie. But please, Captain Sparrow, don’t insist it’s a best practice without reviewing the evidence.

In the next issue, I’ll examine how modern electronics have complicated dark adaptation and discuss an initiative that could someday provide relief.