As a seasoned navigator, I know this basic truth: Your compass is your primary navigation instrument. When all else fails, your compass will still be there.

Most people would say their chartplotter is at the top of the list for navigational tools, and they would be correct. Multifunction displays have become the go-to over the compass and paper charts. Even still, I say the trick is to use the MFD in tandem with your compass.

A compass is a mechanical device that incorporates magnets attached to a rotating card, enabling it to point toward magnetic north. Most compass cards show in 5-degree increments, with headings from magnetic north, to east, to west and back to north. The key indicator is called the lubber line. It shows your present boat heading.

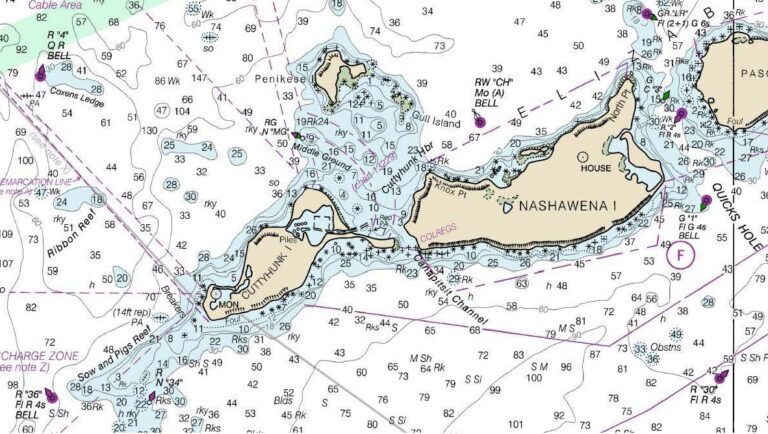

The compass points to magnetic north, not true north. The charts on your MFD show grids oriented to true north (paper charts will be also be there when electronics fail). The difference, which is called variation, will vary with location, and to a lesser extent, with the year. Variation can be found on your printed chart compass roses. With paper charts now fazed out, you will have to update the variation by adding or subtracting the annual change.

You can set your chartplotter to present in true or magnetic direction. I recommend magnetic. Here’s why.

Issues can occur on boats when electronics are installed without considering proximity to the compass. If these components are ferrous or have a current-carrying wire, it can create or alter the magnetic field, leading to deviation, which is an error on the compass. Deviation effect alters based on the heading of the boat, or rather, its orientation with the Earth’s magnetic field. Compass manufacturers know that and provide compensating magnets that can tune out most of those effects.

Knowing all this, it’s better to steer using the compass instead of the chartplotter. The primary reason is that the compass always points to magnetic north. GPS does not know direction; it knows location based on your latitude and longitude. GPS will deduce direction by comparing your present position to what it was a second or so ago.

If you are on a rocking, rolling boat, that direction may not be the course you are taking. Your chartplotter tries to average that out to present Course Over Ground. That is a lagging indicator. Your compass is a leading indicator, and that’s the one you want.

When you select and initiate a course, you know the specific direction you want to steer. If you determine the direction as a magnetic course, you can steer to that using your compass. With a rocking, rolling boat, your compass will quickly indicate the direction the bow is pointed. That will tell you which corrections you need to make to get back to your intended course.

Many experts will tell you to select a distant object in line with your course and steer toward it. That is good advice. But, you must regularly check to be sure your compass is indicating the intended course. If there is a crosswind or current and you continue to steer toward the distant object, you will no longer be on the intended course line. You will be approaching that object from the side. Unseen danger may be lurking along that path.

For the best results, the helmsman should find the right balance between the compass and chartplotter. Navigating by compass is largely a heads-up view, which enables you to keep a lookout. Steering by chartplotter means your view is absorbed in a screen. You should view the chartplotter periodically, not for long periods of time. It’s like taking your eyes of the road to adjust a playlist.

Once you have selected and activated a course, your MFD places a fixed line from the spot of the activation to the selected, active waypoint. As you move along, an icon representing the boat moves on the screen. The orientation of the icon is supposed to represent the direction you are moving.

In addition, a vector line, usually dashed, extends from the boat at a distance you select. It also should be set to present Course Over Ground. It can be set to a time or distance. This vector is the average over time of the instantaneous COG calculations.

That COG vector should be aligned with your intended course line shown on the screen. You can determine that with just a glance. If it is aligned, all is well. Keep steering the intended course using your compass.

If the COG vector is pointed in a different direction, you need to steer to correct for those external effects pushing you aside. Once your COG vector realigns with the steered course, go back to your compass. It indicates the heading (the direction of the boat’s bow). Your boat is “crabbed” to the side, but the boat is actually moving in the proper direction. Continue to steer to that heading using your compass. Periodically check the COG vector on your chartplotter to make sure conditions have not changed.

Using the compass and chartplotter as a team will keep you safe.

This article originally appeared in the September 2025 issue of Passagemaker magazine.