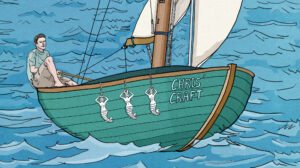

On July 31, 1970, the British Royal Navy ended a centuries-old hallowed tradition: the issuing a daily dram of liquor to sailors aboard its ships, as shown above. According to the Daily Beast, when the day arrived, sailors around the world gathered for a final tot, and the remnants of the barrels were ceremoniously dumped into the ocean.

‘CARIBBEAN BLOWOUT,’ EIGHT MORE TALES FROM DOWN ISLAND

Invented on Barbados in the 17th century as a convenient by-product of the sugar refining process, rum went on to play a major role in everything from the Atlantic slave trade to the American Revolution to the invention of tiki culture. Rum defined British naval tradition and shaped the tastes of American elites during Prohibition. This molasses-based liquor has gone from the original rumbullion—a rough-and-tumble, harsh-tasting drink—to rare bottles of premium aged varieties selling for as much as $54,000 today.

And yet, it has been anything but a steady evolution from swilling to sipping. In fact, it seems that every 50 years or so, rum has swung wildly from being a cheap and horrible-tasting way to get drunk to being rediscovered and claimed as a status symbol.

Through the centuries, one thing has remained constant: Rum has always been the drink of the sea. Produced first on Caribbean islands and then distilled in New England port towns using imported molasses, rum has been strongly associated with sailors, pirates and privateers. Even if the seafaring spirit of most rum today is more marketing spin than genuine connection to the islands and coastal towns where it was once exclusively produced, rum does have a rich and authentic nautical heritage.

Though many classic rum drinks are now more readily associated with their fruity, spring-break spinoffs than their original incarnations, this is the beauty of rum. It’s versatile. It rolls with the punches.

YO-HO-HO

While pirates and rum go together like peg legs and parrots, the most played-up aspect of rum’s maritime history is perhaps a bit exagg-arrrr-ated. Yes, there was a real Captain Morgan (his name was Henry), and he likely drank as much rum as any other sailor. But pirates didn’t seem to be particularly picky about their drink; contemporary accounts rarely mentioned rum specifically. It was a work of fiction, Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Treasure Island” and its refrain of “Fifteen men on a dead man’s chest/Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum,” that cemented the connection between pirates and rum.

If Stevenson used rum symbolically, it was an apt choice. Even if the pirates’ thirst for rum has been overstated, the liquor had long been associated with disorder. While it’s disputed exactly where the term “rum” originated, most agree that it’s related to “rumbullion”—an English word for rowdiness that appeared around the same time as the drink that caused it. An early name for rum was kill-devil, and it’s described in 17th-century accounts as a “hot, hellish and terrible drink.”

RUMBULLION & REVOLUTION

While the image of a rum-drinking pirate easily comes to mind, our Founding Fathers are not usually pictured drinking the stuff—let alone being driven to war over it. When it comes to important beverages, many American history textbooks skip straight from tea to whiskey.

But whiskey didn’t become America’s homegrown liquor until America expanded west to the plains, where the grain crops that failed on the rocky New England coastline could thrive. Before that, nearly every port town had its own rum distillery—or 63, in the case of Boston. The rum they produced was far inferior to Caribbean rum, but it was cheap and potent, and each tavern had its own concoction—including anything from nutmeg and cloves to citrus juice and eggs—to make a more palatable punch. Colonists drank, on average, nearly four gallons of rum each year.

Yet it’s no wonder this aspect of maritime New England history usually takes a back seat to whaling, shipbuilding and textile mills. Rum was a key component of the cruel exchange of human lives for consumer goods, a triangle of trade that linked New Englanders to slavery long after it was officially abolished in the Northern states.

The Boston Tea Party became the symbol of revolt, but the effects of other tariffs were felt more acutely. The Molasses Act of 1733 and the Sugar Act that followed in 1764 increasingly restricted access to cheap molasses sourced from the French-controlled Caribbean islands, threatening the entire domestic rum industry. John Adams famously wrote, “I know not why we should blush to confess that molasses was an essential ingredient in American independence. Many great events have proceeded from much smaller causes.”

Indeed, before the Whiskey Rebellion was the rum-fueled Revolutionary War.

GROG

American colonists loved their rum, but the British Navy was first to make rum drinking official policy. Beer or wine had always been substituted for drinking water aboard ships, but with the conquering of Jamaica in 1655, the Royal Navy began to give out rum instead. Being more alcoholic and therefore less conducive to algae growth, these daily rations of rum, known as tots, held up far better in the tropical heat. The rum held up almost too well. It could be stowed longer, and not surprisingly resulted in more drunken sailors than could easily be stowed in the longboat till they were sober.

Enter Admiral Edward Vernon, wearing a coat made of grogram (a coarse fabric made of mohair and silk, often reinforced with gum for weatherproofing). Knowing he could never get away with decreasing the rum ration, but concerned with the dangerous levels of drunkenness among his crew, “Old Grog,” as he was affectionately known, decided to dilute the tot with water and distribute it over two servings per day.

In 1740, Vernon decreed the ratio four parts water to one part rum and suggested that lime and/or brown sugar be added to the grog (as it was called) to make it more drinkable. It’s possible that this recommended addition of lime juice to improve the taste of grog may have fortified the British sailors, helping them ward off scurvy nearly 50 years before it was discovered that citrus was the cure and lime juice became mandatory.

SIPPING RUM

Rum may come by most of its nautical associations honestly, but over the years, industry marketers have watered down the rich (and at times, deeply problematic) history of the drink into neatly packaged narratives—which may or may not have any connection to reality.

The introduction of Captain Morgan’s in the 1950s marked the beginning of this era, and as Wayne Curtis notes in his 2006 book “And a Bottle of Rum,” today the biggest brands are owned by multinational corporations. He writes, “Party rums are generally stateless and islandless, despite their claims to carrying on the best traditions of Cuba or Puerto Rico or Jamaica. They have no geographical anchorages, but find temporary harbors with international conglomerates.”

But even this is beginning to change as rum is reinvented yet again. Today, it’s easy to find a rum that can be sipped without wincing, and consumers are willing to pay for an authentic backstory as well. Whether it comes from a New England craft distillery embracing regional roots (minus the slave-trade connection) or Caribbean producers touting their centuries-long heritage (minus the slave-trade connection), there is a premium rum for everyone, from the “buy local” beer-and-bourbon bros to the cosmopolitan connoisseurs, ironic-tiki-mug-toting hipsters and basement bartenders.

Of course, one might argue that the through line of rum’s story is really more that it’s always been a cheap way to get drunk. And that tradition lives on as well, even if today’s budget rums are unpalatable in a much different way than the original rumbullion, which by all accounts tasted absolutely nothing like coconut, raspberry, melon or vanilla.

From tots doled out from the scuttlebutt to splashes of Bacardi 151 lit atop glasses of Dr Pepper, rum has a long and varied history of being afloat. And that’s something we can all drink to. It’s six bells somewhere.