I was happy to be delivering my new (at least to me) trawler Betty Jane to Florida, but also a tad concerned. We’d departed Georgetown, Maryland, early that morning, eased on down the Sassafras River, doing 8 knots or so, hit the main channel at Howell Point, and now Betty and I were chuggin’ along well south of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. There’d been no trouble thus far, but hey, my ears were still tightly attuned to the pitch of Betty’s rumbling old Lehman diesel and my eyes kept a beady watch on her rpm gauge.

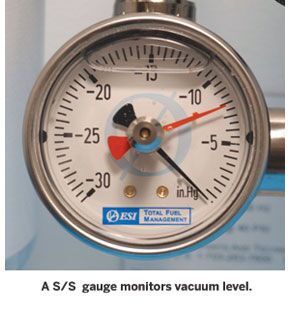

Fuel was the issue. While I’d begun the day by topping off with some nice fresh go-go juice at Duffy Creek Marina, I’d piled it on top of some old, residual stuff. And because the long trip south was so darn rushed, I’d also failed to take some very sensible pre-departure measures I’d have surely taken had there been a little more time to play with dockside, like adding vacuum gauges to Betty’s Racor fuel filters and hiring a local tank-cleaning outfit to fall by and polish her antiquated fuel and spruce up the tanks that the stuff had grown antiquated in.

“Just in case the worst happens,” I’d chortled to my lone crewmember Chuck in Georgetown just a couple of days before, while stowing a big bag of filter elements in a locker, a slap-dash fix for a slap-dash embarkation. Chuck had given me a gloomy look. The ripples in our slip at the marina were already beleaguering him with mal de mer and, as a result, I feared he might make “a pier-head jump,” as we used to say in the Merchant Marine, before our journey even began.

Click Here To Learn More About Arawak‘s Refit

Of course, the worst did happen. Just before sunset, as we cruised south on the Chesapeake, the trusty old Lehman started to snort, cough, and lose rpm. Then, a split second before I had a chance to pull the throttle back and mash the engine-stop button, the darn thing simply quit.

“Oh no,” Chuck would have heard me say, had he not been lying prostrate in the saloon below while I easedBetty out of the channel and single-handedly dropped anchor. “Fuel filter’s plugged.”

The Glories of Fuel Polishing

I learned lots of things as that evening wore on. But perhaps the most pivotal of the lot manifested in a very dramatic way immediately after Betty and I arrived at Bay Point Marina in Panama City Beach, in the great state of Florida. In hopes of never again having to bathe in diesel fuel by moonlight while struggling to restart an august, unfamiliar, air-locked diesel engine, I had a local diesel service install a brand-new fuel-polishing system. Fuel-polishers, I was now convinced, were important onboard companions. Right up there with magnetic compasses, paper charts, and PFDs.

Which is not to say, certainly, that products from companies like Racor and Separ, with their touted, never-to-be-disparaged centrifuging, coalescing, and filtering functions, are not important as well. But even if installed in pairs or threesomes for the sake of safety and redundancy, such devices simply can’t do what most dedicated fuel polishing systems do—primarily because they’re not meant to.

By way of getting a handle on this, let’s briefly consider the fuel-polishing units manufactured by ESI Total Fuel Management, a Virginia-based company that’s supplying a polishing system for Arawak, the Grand Banks 42 Motoryacht we’re presently rehabbing (check out MyBoatWorks at www.betterpowerboat.com for an update on the project) down in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Filters Versus Polishers

Today, ESI uses its roots in the oil business and commercial shipping to service a stable of international customers (from big banks to giant internet providers) that demand super-reliable fail-safe diesel-fired electrical power. However, despite the broadness and immensity of ESI’s present scope, ESI honcho Alex Marcus remains intensely committed to his company’s original, startup venue—fuel-polishing technology for recreational watercraft—and he definitely enjoys talking about the subject.

“Just about every boat with an engine,” he explains, “has two fuel-related systems onboard. The first entails the delivery of fuel to the powerplant—it typically includes one or more products from Racor, Separ, or some other manufacturer. And, if that’s all there is onboard, then that product is the one and only line of defense between the powerplant and the particulate matter and other contaminants that are likely hiding in the fuel tank.”

Fuel-polishers, however, are wholly different, according to Marcus. They deal exclusively with what he calls “the second fuel-related system onboard,” i.e. fuel storage in a tank or tanks. And they do this, he adds, by performing treatment functions that a basic separator or filter, even if installed in duplex or triplex mode, simply can’t.

To be more specific, Arawak’s CFS1000FRE fuel-polishing unit will remove (via a Racor 1000MA filter with cellulose/glass-fiber media) all particulate matter down to an exceptionally fine 2 microns; will separate (versus aboarb) 99.95% of all water, both free and emulsified; and will permanently nix all yeasts, algae, fungi, and other organisms via a De-Bug L-1000 multi-magnetic array. Moreover, the unit has a high-flow continuous-duty pump that is tweaked to optimally agitate contaminates in the boat’s fuel tanks during the system’s operation, thereby facilitating total, as opposed to partial, processing.

Why are these extra functions so critical? Sure, a basic separator or filter will efficiently massage fuel while a boat is being operated, but it will just twiddle its thumbs during the long periods she sits idle in her slip. And it’s during these periods that condensation adds water to the fuel, which then helps problematic organisms propagate into filter-clogging sludge. A grim scenario? Even grimmer if we’re talking modern, high-pressure, common-rail diesels that are seriously finicky about the purity of the fuel they ingest.

“And remember,” says Marcus. “Our equipment works whether the boat is operational or not. An owner can clean his fuel while he’s watching TV in the salon, say, or sitting in the wheelhouse punching in waypoints.”

Cool and Specific Virtues

There are reasons why ESI and the fuel-polishing equipment it sells is so popular today. As already mentioned, long experience at providing clean fuel services (from the refinery straight through to the actual operation of a given piece of equipment) to large nonmarine entities with critical power needs produces some cool cachet. The fact that worldwide enterprises, like Verizon Wireless, Citibank, and Saudi ARAMCO, as well as some 20 or so boatbuilders, all rely on ESI products is pretty impressive.

And then there’s ESI’s engineering. The pumps used in units like Arawak’s CFS1000FRE, for example, are of the run-dry type, thus obviating chances of a meltdown should a user start polishing and then forget while a Racor clogs or some other bit of mischief obtrudes.

Then, ESI uses no threaded-type, leak-prone fittings in any of its fuel-polishing systems. Instead, system components are joined with tight-sealing, O-ring, face-seal-type, hydraulic fittings that can be both tightened to spec and properly oriented or positioned simultaneously. And what’s more, all of ESI’s systems are certified leak-proof prior to sale by Parker-Hannifin (Racor’s parent company), acting as an official third-party.

Also, manifolds are ESI-machined from blocks of aluminum and fitted with hydraulic-type quarter-turn ball valves made by Parker; all wiring involved is of marine-grade tinned copper; and hoses used are of top-end, fire-rated, U.S.C.G.-approved rubber. Top quality stuff. No question!

And finally, because even clean fuel burning in new engines produces gums, resins, carbon, and other problematic substances, ESI recommends and purveys for each of its polishing systems an industrial-grade additive called PRI-D—it does an excellent job of stabilizing fuel when stored for long periods, maintaining its lubricity and power through more complete combustion.

What Price Glory?

Given all of this sweetness and light, it’s no great surprise that the equipment ESI builds and sometimes custom designs for recreational-type engine rooms does not come cheap.

Consider the CFS1000FRE destined for Arawak—it lists for a cool $3,595. Add to that two three-valve manifolds (so fuel can be transferred from tank-to-tank as well as polished) for $2,354; drop tubes and associated components (to circulate fuel through the entire polishing system efficiently) for $1,908; U.S.C.G.-approved Parker hoses (with detachable swivel fittings) for $2,422; and (with shipping and handling) you’re looking at a total of $10,455. Just for parts and equipment.

“Expensive—perhaps,” concludes Marcus. “But when you consider the alternative—the problems that can arise when a powerplant fails because you’ve only got one real line of defense and you and your loved ones are onboard—maybe not so expensive at all.”

ESI Total Fuel Management,

703-263-7600; www.fuelmanagement.com

Parker,

800-272-7537; www.parker.com

My BoatWorks Project (Arawak refit)

This post originally appeared in our affiliate, Power & Motoryacht, and can be seen here.